Memorandum

City of Lawrence

City Manager’s Office

TO: David L. Corliss, City Manager

CC: Diane Stoddard, Assistant City Manager

FROM: Roger Zalneraitis, Economic Development Coordinator/Planner

DATE: January 10th, 2011

RE: Gas Prices and Lawrence

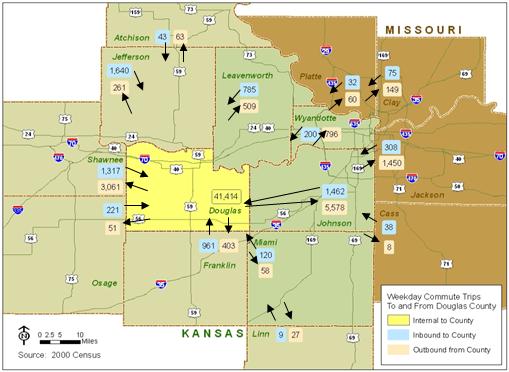

Last week, Mayor Mike Amyx inquired about the potential affect that increased gas prices could have on Lawrence. The concern was driven in part because of commuting patterns. As seen in this map, in 2000 there were over 5,000 in-bound commuters to Douglas County, and more than twice that number of out-bound commuters:

Map

provided by Mid-America Regional Council (MARC)

Rising gas prices could cause commuters to locate closer to work. Since more people commute out of Douglas County than in to Douglas County, higher gas prices could cause these commuters to leave Lawrence, reducing or even reversing our population gains.

The following analysis looks at the ways people could respond to gas prices and investigates whether people may have responded to the rising gas prices of 2007 and 2008 in any of these ways. While nothing definitive can be concluded, it appears that commuting patterns have changed but not to the detriment of Lawrence.

High Gas Prices and Consumer Responses

There are three ways that people could respond to higher gas prices:

1) People could choose to commute less by either finding a new job closer to home, or moving closer to their existing job;

2) People could choose to buy a more fuel-efficient vehicle or shift to an alternative form of transportation, such as carpooling, public transit, or bicycling/walking; or

3) People could “do nothing” and either reduce their savings, or reduce their spending on other items.

The question is, as gas prices rise, how have Lawrence residents responded?

Did residents shift their spending?

I cannot answer whether people have reduced their savings, or shifted spending from other goods. I have access to spending data in 2009, but no data earlier to that. There is some sales tax data available. However, gasoline is not subject to sales tax in Kansas, and it is difficult to determine from sales taxes alone whether or how residents have been shifting their purchases as a result of higher gas prices.

Nonetheless, I think it’s reasonable to assume that some residents have reduced their expenditures on other items, or their savings, to pay for higher gas prices. More than likely, people would do this if they thought it was the cheapest option available. This would happen for residents who thought that the change in gas prices was temporary, who believed that alternative modes of transportation took longer, and who put a high value on keeping their commutes short.

Did residents relocate closer to their jobs, or find jobs closer to their home?

We can look at data from the American Community Survey (ACS) to see if people are moving more frequently. In this case, I looked at the one year 2006 and 2009 ACS data. The question asks whether people have moved or not in the last 12 months. Thus, the 2006 data would look at whether people moved in 2005, and the 2009 data would look at whether people moved in 2008. These dates are important, as 2005 largely pre-dated the run-up in gas prices, while 2008 was right in the heart of the record-high gas prices (The 2000 Census only asked about movement in the last five years. Thus this data was not comparable):

It would appear that there was some increase in mobility from 2006 to 2009. The number of people living in the same house as a year ago fell slightly. This was largely attributed to people moving within Douglas County. This could be, for example, people moving from either one town in Douglas County to Lawrence, or people moving within Lawrence itself.

Even if people are moving, are they moving closer to their jobs? First, using the ACS data we need to understand the total number of workers and commuters in Lawrence. According to the ACS, there were just over 48,000 Lawrence residents in 2006 who were 16 and over and worked. In 2009, this total was slightly higher, likely just over 49,000 working residents age 16 and over.

The following table looks at where these residents of Lawrence work:

In 2000, just over 73 percent of all employed Lawrence residents worked in Lawrence. This appears to have fallen slightly in 2006, when about 70 percent of Lawrence residents worked here. That means that of the 48,000 residents working at the time, about 34,000 of them worked in the City and the remaining 14,000 or so commuted. However, in 2009, over three-quarters of all residents worked in Lawrence[1]. This means that of the 49,000 residents working, only about 11,000 commuted. This represents a decline of 3,000 commuters at the same time that the number of residents working increased slightly. It thus appears that Lawrence residents were commuting outside of the City and County less in 2009 than in 2006.

Is this change a result of people living in Lawrence getting new jobs closer to home, or is it the result of residents who lived in Lawrence moving closer to where they worked outside of the City? We cannot definitively answer this question. However, when we consider the first chart, it doesn’t appear that people were moving into Lawrence or Douglas County with any greater frequency in 2009 than they were in 2006. There is some evidence that intra-county movement increased, but not inter-county movement. Since inter-county mobility did not increase, it is less likely that higher gas prices were causing a greater number of people to move closer to their job, and more likely (the table “Where do Lawrence Residents Work”) that people were finding jobs closer to where they already lived. Intuitively this has some sense, as it is less costly to change jobs than it is to move, assuming the income available from each job is about the same.

Of course, the most important reason commuting patterns could change is a shift in the location of jobs. As we all know, the nation entered a recession between 2006 and 2009. Locally, if one county was not affected as badly by the recession as other nearby counties, this could affect commuting patterns. Since Douglas County’s unemployment rate is comparatively low for the region, perhaps our share of regional jobs increased, reducing the likelihood of commuting.

Data from the BLS suggests that this is not the case (please see chart, next page). The four counties on the chart- Douglas, Johnson, Shawnee, and Jackson, Missouri- represent both our own county and the three nearby counties that comprise the vast majority of commuters from here. The total number of jobs in these counties has declined from about 813,000 in 2006 to just over 796,000 in 2009. However, there has been very little change in the share of jobs found in each County. Jackson County saw a slight decrease in its share of regional jobs, while Johnson and Shawnee Counties saw a slight increase. The share of jobs in Douglas County remained unchanged. If commuting patterns changed as a result of a shifting location of jobs, the likely outcome suggested by this data is that there would be a higher probability of commuters going to in-state counties instead of Jackson County (Kansas City), Missouri.

Did residents change the way they get to work?

The final option people have for dealing with higher gas prices is to reduce gas consumption through more fuel efficient vehicles or through finding alternative transportation methods to work (carpooling, transit, walking/bicycling). I do not have access to car sales data at the local level, but national data showed that there was a move toward more fuel efficient vehicles during the gas price run-up in 2007 and 2008 (see, for example: http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,365714,00.html ). It is highly likely that similar trends occurred both in Kansas and in Lawrence.

The ACS does provide data on different commuting methods, however. The following table breaks out commuting methods by the most prominent ways people use to get to work:

Between 85 and 90 percent of Lawrence residents drive to work. There may have been a slight decrease from 2006 to 2009, but the data is not statistically significant and it almost identical, anyway, to the percentage of residents who drove in 2000. Interestingly enough, the percentage of residents who carpool versus drive alone has not changed in 10 years (the data wasn’t shown because there was no change). About 90 percent of all residents who drive, drive alone. There was an increase in the number of residents who bicycled. However, the most notable increase was in the number of residents who worked at home. The change from 2006 to 2009 was statistically significant, suggesting that more Lawrence residents are working at home than before.

What about people who worked outside of Douglas County: did their commuting methods change? As we saw, the number of residents working outside the County declined from 2006 to 2009. It also appears that how the remaining commuters got to work may have changed as well:

About 99 percent of all inter-county commuters either drove alone or carpooled in 2006. This appears to have fallen to about 95 percent in 2009. The balance was made up entirely by people either taking a taxi, or public transit. Thus in addition to fewer outbound commuters, there also appears to be a larger number of outbound commuters using public transit than before. Part of this may be because of the new K-10 commuter bus service that runs from Lawrence to Johnson County Community College in Olathe.

One additional possibility is that some people who used to commute began to work from home. We saw that the number of residents working from home increased. However, when I looked more closely at the data I found the following two, seemingly contradictory, results:

1) the increase in people working from home was largely home owners, as opposed to renters; and

2) the increase in people working from home was largely people making less than $10,000 per year.

It doesn’t seem like people who make less than $10,000 per year are the most likely candidates to be offered jobs where they can work from home. We typically think of these as service-level jobs that require attendance. On the other hand, some jobs have highly variable income and do not require people to be at a particular location to do their work, such as positions in insurance. The income in these positions may have been adversely affected by the recession. These types of jobs could account for some of the increase in people working from home who made very little money. Thus it may be possible that some former commuters are now working from home.

Conclusion

The ACS and BLS data presented cannot “conclude” that gas prices have been responsible for any of the changes shown. As noted, I looked at 2006 and 2009 because these years came just before and immediate during or even after the most recent run-up in gas prices. Despite the lack of conclusiveness, the data does show that:

1) there was an increase in intracounty mobility during this period;

2) the number of intercounty commuters declined substantially;

3) of the remaining intercounty commuters, a reasonable number began to use public transit. However, carpooling does not appear to have increased; and

4) there is some possibility that a few former commuters may now be working from home.

These results mean that it is possible that higher gas prices contributed to changes in where people chose to live and work as well as how they elected to commute. It is also likely that some residents bought more fuel-efficient cars, and other residents changed their savings and spending patterns to account for higher gas prices.

If higher gas prices were responsible for these shifts in commuting and work location, and people prefer to find jobs closer to home rather than move, one possible implication is that we have to maintain good job opportunities locally in order to keep residents from either seeing a deterioration in their income (or to reluctantly move). Another potential implication is that public transit has helped people who still commute outside the City. If these two conditions really do help insulate Lawrence from high gas prices, some important policy considerations would be to continue to pursue a healthy local job market and to maintain- and possibly expand- commuting options for residents.